History

A royal beginning

During the 17th and most of the 18th century, performing arts in Sweden is purely an elite activity, and the small amount of opera, theatre and ballet that exists is an affair wholly internal to the royal court, almost always in French. The person who would come to change that is the highly cultural-minded King Gustav III. Among many other important cultural institutions, he establishes the Royal Opera House in 1773 and the Royal Dramatic Theatre in 1787, both with the express mission of producing performing arts entirely in Swedish. From the year of their establishment, both theatres are also responsible for training opera singers and actors, respectively, which would continue to be the case well into the 20th century.

Not all Swedish rulers have the same passion for the theatre as Gustav III. The fate of the opera and theatre goes up and down, theatres are demolished and burn down, state subsidies come and go. For 70 years, until 1888, the Dramatic Theatre and the Opera share a common organisation. The teaching of opera switches back and forth between the Opera and the Conservatory of the Academy of Music, until from 1942 the two co-operate on running a joint opera class. At the Dramatic Theatre, the organisation is more stable, and under a long series of principals, most of them women, the Royal Dramatic Theatre training academy becomes the mainstay of Stockholm's acting education for the 19th century.

New ideas and breakouts

In the mid-1960s, a number of factors – international trends, new technologies, increasingly independent public officials like Harry Schein and Roland Pålsson, and a favourable government – coincide to give a boost to those who want to innovate and change the rather outdated world of artistic education.

In 1963, some of the most important names in Swedish dance, Birgit Cullberg, Birgit Åkesson and Ivo Cramér among them, are given the opportunity to start a pure, contemporary choreography programme as part of the Academy of Music, dubbed the Institute of Choreography. The following year, the dance pedagogy programme already run by the Swedish Dance Teachers' Association is also linked to the Institute, and in 1966 a training programme for mime artists is initiated. The Swedish Film Institute – with the support of a government which harbours similar plans themselves – starts Sweden's first film school in 1964, called simply the Film School. The premiere lecture was, of course, held by Ingmar Bergman.

The spirit of the time also includes bringing programmes under public management to strengthen them and securing their long-term funding. In 1964, the training academy at the Royal Dramatic Theatre brakes away, along with similar academies around the country, to form the independent National School of Acting. In 1968, the opera programme at the Royal Academy of Music makes the same journey and became the National Musico-Dramatic School, followed quickly by the dance programmes, which become the National School of Ballet Dancing in 1970. Finally, and perhaps most drastically, in the same year the government implements its longstanding plans for a state school bringing together education in television, film, radio and theatre, under the name Swedish Institute of Dramatic Art. In connection with its launch, the Film School is closed down and many of the teachers move there instead.

All the components that will become SKH are now independent institutions under public management.

A major higher education reform

It is not long before these newly-formed organisations go through their next fundamental change. In 1977, after a decade of preparatory work, the government launches a major reorganisation of post-secondary education. All programmes, practical as well as theoretical, were to have the same form – they were to become higher education institutions. Twelve new colleges are established.

The artistic schools in Stockholm are originally intended to be merged into a single organisation, but after major protests the existing units are retained, albeit as individual higher education colleges. The Institute of Dramatic Art retains both its name and specialisation, and the National School of Ballet Dancing takes the name University College of Dance. While the acting schools in Gothenburg and Malmö are incorporated into the University of Gothenburg and Lund respectively, the one in Stockholm becomes completely independent for the first time, as the School of Acting, Stockholm. The opera school follows suit and becomes the Musico-Dramatic School, Stockholm, for a long time Sweden’s smallest university college. Later, in the 1980s, they became the National Academy of Acting and the University College of Opera respectively.

It is also in connection with the higher education reform that artistic research makes its debut in Sweden. During the consultations leading up to the launch, the arts schools push hard to ensure that research carried out as part of artistic practice – at the time referred to as development work – is given a prominent place in the new Higher Education Act. Artistic research will play a major role when SKH finally comes into being.

Exchanges and incentives

These higher education institutions in the arts change constantly over the following decades. The Institute of Dramatic Art initiates a number of specialised programmes in theatre technique, film editing, production, documentary film and scriptwriting. In the early 1990s, the University College of Dance launches both a dance therapy programme and – after almost 30 years of discussions – a programme for dance performance. At the same time, the mime acting programme moves to the National Academy of Mime and Acting, which also offers an acting course in sign language for the first time in Swedish history. In the 2000s, another long-discussed programme, for contemporary circus artists, is launched at the University College of Dance, which consequently changes its name to the School of Dance and Circus in 2010.

The next major higher education reform in 2007 means that, in the wake of the international Bologna process, all programmes at the various schools are to be of equal length, with bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees. Artistic research is now also being further prioritised, and the revised Higher Education Act gives the artistic basis for research the same status as the scientific. The possibility of doctoral education on an artistic basis has also been opened up for the first time. Several institutions, including the School of Dance and Circus, apply to conduct postgraduate education, but they are simply too small to be able to do so yet.

What can be done to create an environment that is large and viable enough to support artistic research? The solution is to initiate a merger with the support of a reorganisation-friendly government, something that is already in the air and has been going on for a long time in our neighbouring countries. First out is the National Academy of Mime and Acting and the Institute of Dramatic Art, neighbours on Vallhallavägen, which merge in 2011 as the Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts. And after long talks and in-depth discussions about scope and form, Stockholm University of the Arts finally comes into being in 2014, when the Stockholm Academy of Dramatic Arts, the School of Dance and Circus and the University College of Opera merge into a single organisation.

A united university

Just a couple of years after the merger, the new research environment bears its most sought-after fruit when, in 2016, SKH becomes the first higher education college in the arts in Sweden to be authorised to issue doctoral degrees. The same year, a system of four profile professors at an interdisciplinary research centre has also been established. By 2018, an international research conference in the form of Alliances and Commonalities has been launched, and a journal for artistic research, VIS, is now being published. External research funding is increasing significantly, and external researchers are beginning to use SKH as a location to base their research in.

At the same time, co-operation is deepening. After initially being mostly an umbrella structure, more and more activities are placed in the joint organisation, where new procedures and working methods are developed to meet the challenges of the increasingly transdisciplinary arts world of the future. In 2018, education is brought together under a common structure, and from 2020, the names of the former universities no longer are used. At the turn of 2023, another major reorganisation takes place, with seven extant departments becoming two new ones, crossing the old institutional borders.

And the first preparations are now made for a final step to bring SKH fully together. In 2018, work begins on creating a joint university environment in a new building, which (after land allocation and an architectural competition) is now planned to be located in Slakthusområdet, to be inaugurated in 2029. With firm traditions and in constant change, Stockholm University of the Arts continues to develop and move towards the artistic world of the future.

Dance practice at the Royal Dramatic Theatre training academy 1937. From the left Barbro Kollberg, Ingrid Berthen, Gullan Granhult, Georg Årlin, Ziri-Gun Eriksson, Toivo Pawlo, on the floor Ulla Wikander. Photo: Pressens Bild

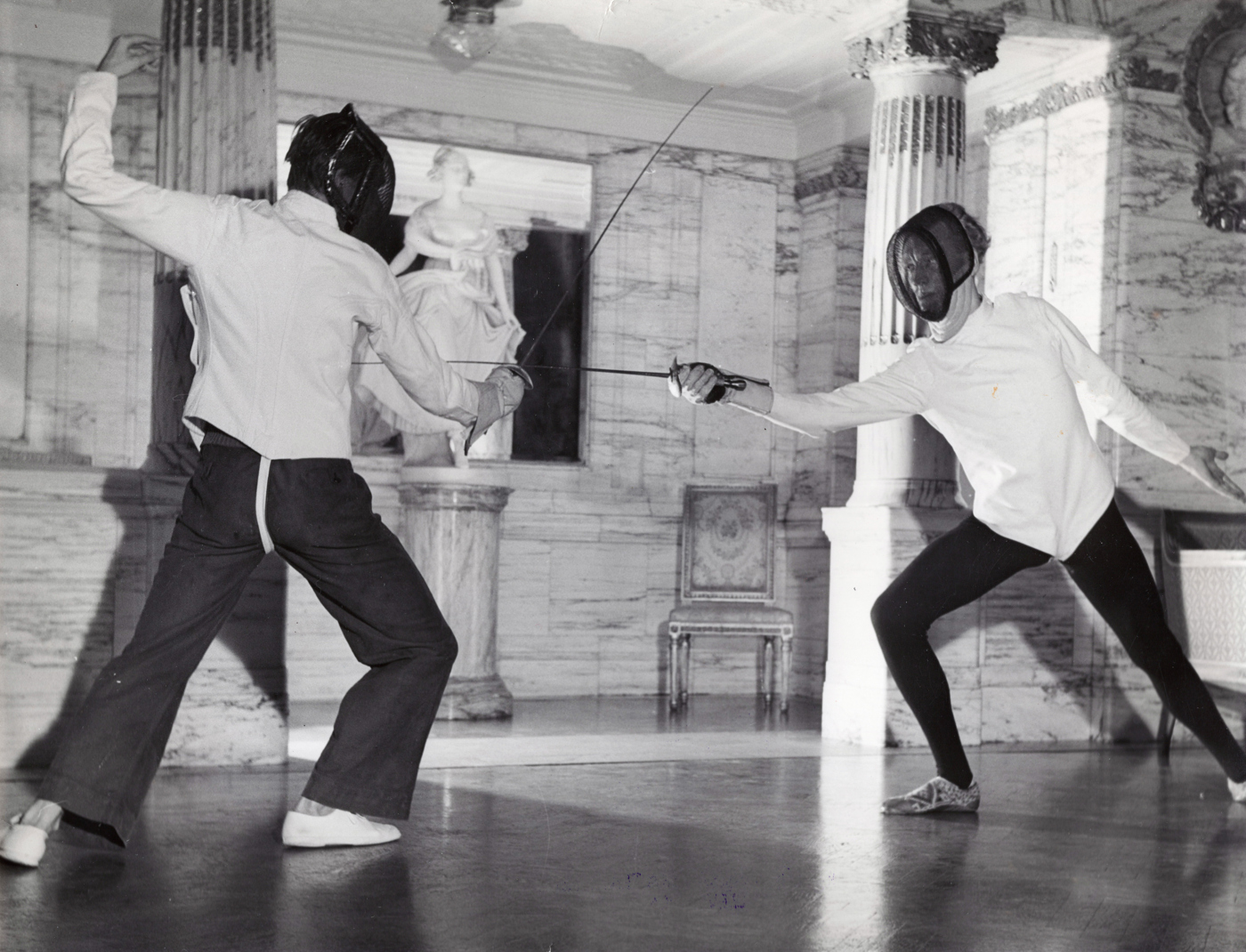

Max von Sydow, on the right, fencing against Jan Olof Strandberg in 1949-50. At the training academy fencing was always on the curriculum. Photo: Sven Gillsäter

Ingrid Thulin and Margaretha Krook, future stars of stage and screen, playing around at the training academy in the early 50s. Unknown photographer

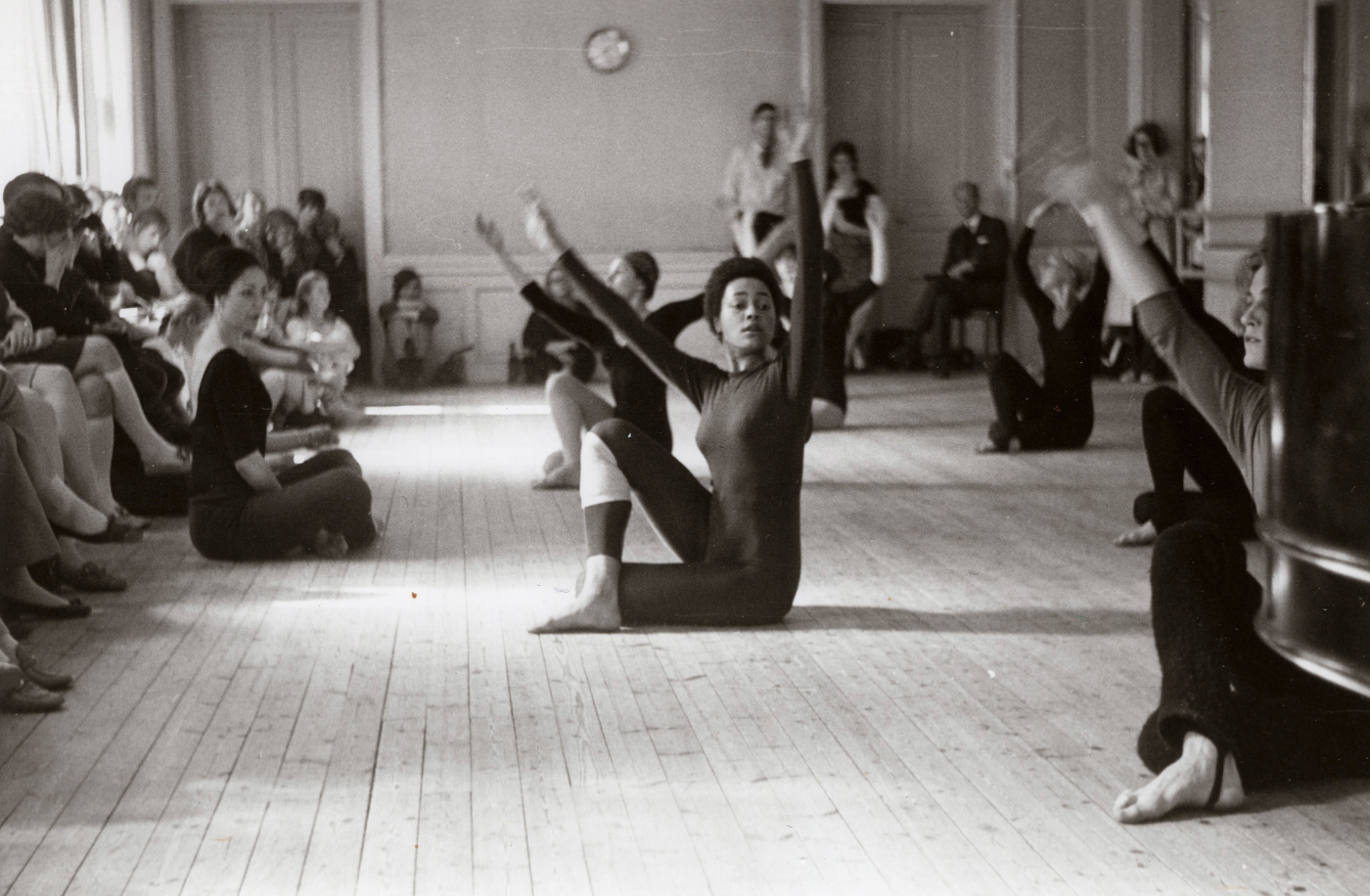

A lesson in Graham Technique with the Julliard-based guest teacher Patricia Christopher at the Institute of Choreography in the late 1960s. Photo: Monica Nilsson

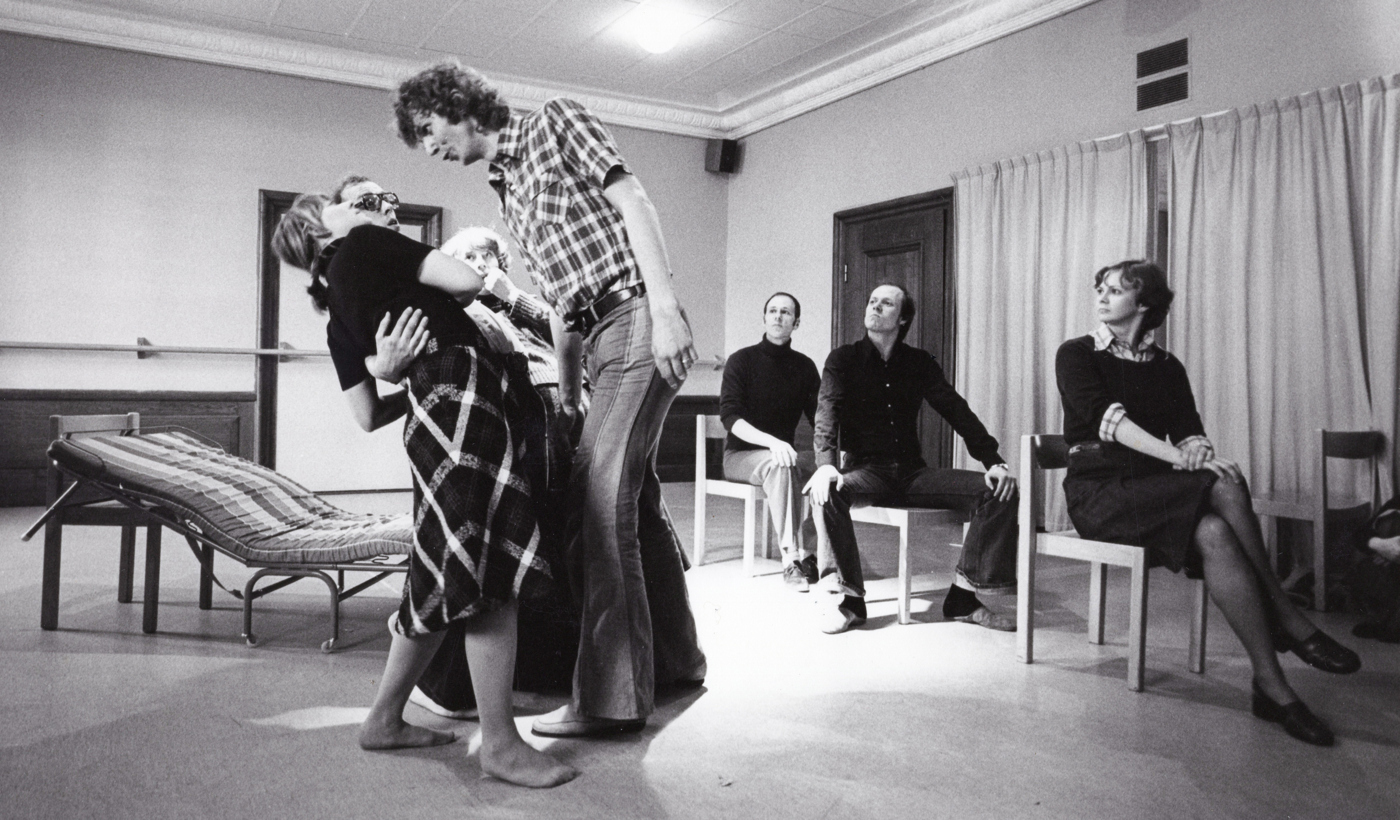

-Arehn%2c-Regi-Mats-Ek%2c-Paris-och-Helena-1972%2c-Statens-musikdramatiska-skola%2c-K1-1%2c-fotograf-Beata-Bergstr%c3%b6m.jpg)

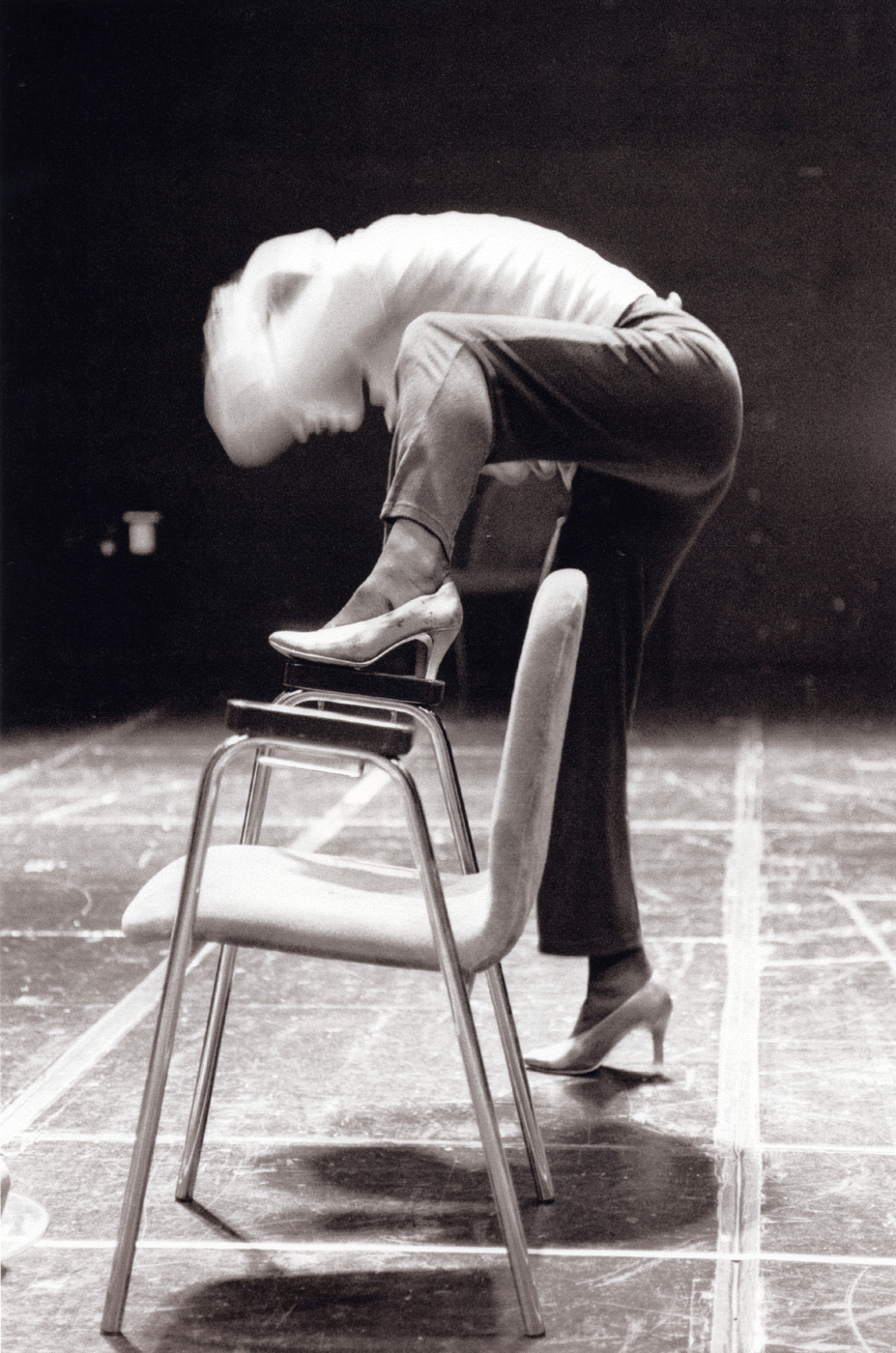

%2c-STDH%2c-ur-Mihra-Lindbloms-samling.jpg)

Mask and wig designer Thea Kristensen practices disguise, Institute of Dramatic Art, mid 00s. Photo: Mihra Lindblom